In the News:

Donna Ferrato

Yesterday TIME published the long waited list of the 100 Most Influential Photographs of All Time. Last week I had the pleasure of interviewing photojournalist and activist Donna Ferrato for New Zealand Pro Photographer (out January), and she told me how thrilled she was to have a picture in this collection.

The photograph (below) was taken in 1982. Donna was shooting a story on swingers for Playboy and suddenly the scene erupted into violence. Donna says "I also was thinking if I get a picture of this, at least people will believe that it really happened”. This photograph propelled Donna into a lifelong journey to fight for the rights of women and to raise awareness of the terrible impact of domestic violence on women and children. It was first published in 1991 in her book Living with the Enemy. I can't say more about my interview with Donna until it is published, but she's one hell of a photographer and an amazing person.

The TIME special edition is also incredible. Each photograph has a backstory and there are also videos. This link will take you to Donna's story on the TIME site.

(C) Donna Ferrato

Book Review:

Stuart Franklin - The Documentary Impulse

Former president of Magnum, photographer Stuart Franklin was this week named the chair of the 2017 World Press Photo jury. I interviewed Stuart recently for a profile piece in New Zealand Pro Photographer. I also reviewed his book for the magazine and thought I'd share it with you this week.

In 1974 W. Eugene Smith said, “…to some, photographs can demand enough of emotions to be a catalyst to thinking”. This statement underpins the motivation for many documentary photographers as is demonstrated in Stuart Franklin’s ‘The Documentary Impulse’.

Franklin is a photojournalist, or documentary photographer, although labels seem superfluous in this context. Both work to capture the world as it is, and shine a light on subjects that are often invisible. A member of Magnum Photos, Franklin is famous for the photograph known as Tank Man, which he shot from a balcony overlooking Tiananmen Square in 1989, although his oeuvre is far greater than this single iconic image.

The desire to show the human condition in all its glory, horror and multiple truths is, says Franklin, what propels photographers to cover stories of war and conflict, natural disaster, and social injustice. Throughout the book he uses a range of examples to convey the lengths that photographers go to in order to create visual narratives that will hopefully move people to act.

In ‘The Documentary Impulse’ the usual suspects are present, those heroes and heroines of documentary photography that appear in every recounting of photographic history; the aforementioned Smith, Dorothea Lange, Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis as well as more contemporary photographers including Don McCullin, Sebastiao Salgado and James Nachtwey. While it is impossible not to mention the luminaries of the field, this book is not a rehash of existing material.

The most interesting aspect of the book is the discourse around deception and what passes for documentary photography. Manipulation in photography stems back to the medium’s nascent years as Franklin acknowledges, but he quickly moves the conversation on to address contemporary forms of manipulation including military embeds and the staging of events or scenes and how these can impact the reading of an image.

In the chapter on staging Franklin references the work of Gregory Crewdson to ask if there are any boundaries for documentary photography? The suggestion is there isn’t, the implication being the visual literacy of the audience is great enough to read the complex layers of a picture and unearth its multiplicity of meanings. That may be a leap too far in an image-saturated world where the viewing time of images can be clocked in seconds.

Ultimately visual storytelling is personal, but the commonality is our humanity. This is where the documentary impulse stems from and where the power of the photograph resides.

Franklin is a photojournalist, or documentary photographer, although labels seem superfluous in this context. Both work to capture the world as it is, and shine a light on subjects that are often invisible. A member of Magnum Photos, Franklin is famous for the photograph known as Tank Man, which he shot from a balcony overlooking Tiananmen Square in 1989, although his oeuvre is far greater than this single iconic image.

The desire to show the human condition in all its glory, horror and multiple truths is, says Franklin, what propels photographers to cover stories of war and conflict, natural disaster, and social injustice. Throughout the book he uses a range of examples to convey the lengths that photographers go to in order to create visual narratives that will hopefully move people to act.

In ‘The Documentary Impulse’ the usual suspects are present, those heroes and heroines of documentary photography that appear in every recounting of photographic history; the aforementioned Smith, Dorothea Lange, Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis as well as more contemporary photographers including Don McCullin, Sebastiao Salgado and James Nachtwey. While it is impossible not to mention the luminaries of the field, this book is not a rehash of existing material.

The most interesting aspect of the book is the discourse around deception and what passes for documentary photography. Manipulation in photography stems back to the medium’s nascent years as Franklin acknowledges, but he quickly moves the conversation on to address contemporary forms of manipulation including military embeds and the staging of events or scenes and how these can impact the reading of an image.

In the chapter on staging Franklin references the work of Gregory Crewdson to ask if there are any boundaries for documentary photography? The suggestion is there isn’t, the implication being the visual literacy of the audience is great enough to read the complex layers of a picture and unearth its multiplicity of meanings. That may be a leap too far in an image-saturated world where the viewing time of images can be clocked in seconds.

Ultimately visual storytelling is personal, but the commonality is our humanity. This is where the documentary impulse stems from and where the power of the photograph resides.

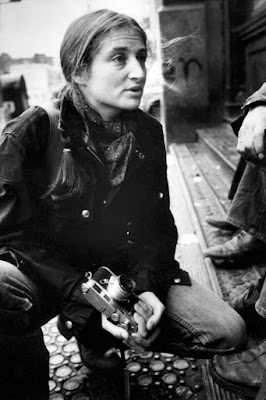

Q&A with Susan Meiselas

Caption: The American photographer Susan Meiselas

Credit line: Courtesy of Jean Gaumy/Magnum Photos

Credit line: Courtesy of Jean Gaumy/Magnum Photos

Another piece I wrote for New Zealand Pro Photographer was a profile on Susan Meiselas. Last year Susan and I were going to meet after Paris Photo, but of course the tragic events in Paris on the night of Friday 13th November threw plans into disarray. Finally almost a year later we got to talk and she shared with me her thoughts for the section "What I Know Now". Here's the Q&A.

Who or what taught you the most early on in your career? What taught me the most was just working. When I look at what is very common now – internships, mentors, workshops – there’s a whole culture of supporting emerging photographers, but that wasn't in place when I started out. Being in the field and confronting questions and problems and trying to solve them, that’s what really taught me the most.

What was the biggest career risk you took? Obviously there are different kinds of risks, there’s the physical and also the psychological. When I began working with the media it was a different culture to the documentary process I’d come from. The risk, specifically with Nicaragua, was that my judgement to stay for an extended period of time was not understood. As a career choice it might have been better to move around a lot to different kinds of conflicts in that classic photojournalistic way. But I didn't really define myself like that. I wanted to invest and to immerse myself.

Which of your personal projects taught you the most? That’s a difficult question because I learn such different things from each project. When I was doing the work with carnival strippers, taking the time to build relationships was probably the lesson. But I’ve learned the most I guess from the Nicaragua work because time has been such a factor in my perspective.

Do you consider you have a particular style? I have an approach, but I’m not interested in style per se. I’m not sure I want people to be thinking this is a Meiselas photograph versus being engaged with what’s in the frame. My intent is to be successful in creating a kind of narrative space.

How do you define approach? It begins with finding something I’m curious about, often for reasons I’m not even sure of. It could be a particular group of people such as a project I did very early on, that few people know about. It was on a group of Santa Claus’ from the Bowery in New York near where I live. Or it could be about a place like Nicaragua, a culture in transition, a social conflict evolving. I’m drawn often to history and the evolution of an historical process like in Kurdistan. So my approach is building off that curiosity a set of relationships and engaging over time.

Can you define what has been the most artistically or personally satisfying work that you’ve done? I can’t judge one project over another. I’m not invested in having the same style or representation of the work. In fact I am more committed to exploring different approaches to represent the ideas I’m trying to make more visible. The aesthetics may change, so for example the work I did on the border of the US and Mexico was done with a panoramic camera, which creates a different dynamic. I think the aesthetics are influenced by what I’m trying to achieve with the work.

When you started out did you have an idea of what you wanted to do, did you think you were having a career? No not at all. First of all I started doing photography in a teaching environment and I was very interested in what we called at the time visual literacy. At that time I was not so much focused on my own work, although I was doing that on the side; that’s when I began the carnival stripper work. I stayed with teaching for a number of years, but I didn't see myself as a teacher in the long term. I didn't have a road map to how to be a photographer for life. That’s what I’ve done but I didn't know how to get there.

What turned out to be the most helpful thing you did to advance your career? The invitation to join Magnum was a definite shift and created many different kinds of opportunities, but most importantly a community with which I’ve related for forty years. There’s something about Magnum’s integration of multiple generations, which is particularly special and watching those lives evolve, and looking at the sustaining choices they’ve made in their practices, that’s invaluable. It’s not always what you talk about, but what you see around you. There’s a lot of diversity in Magnum more than similar notions of photography.

What's the most important thing you could tell someone about creativity? That it comes from within, it’s the process of engagement with what you see, and it’s about interaction. Ultimately creativity is solving the problems you create for yourself.

What’s your next big challenge in the world of photography? Participatory media interests me a great deal. I’ve just reprinted the third edition of the Nicaragua book with Aperture, which will have a modest augmented reality element. The pages of the book have icons and you download a free app and from the image on the page you can link to a short film clip from the film I made ten years after the first Nicaragua book. So you’ll have this interaction of a still photograph and the moving image. I’m quite curious to see how that activates audience engagement with the material.

-->Who or what taught you the most early on in your career? What taught me the most was just working. When I look at what is very common now – internships, mentors, workshops – there’s a whole culture of supporting emerging photographers, but that wasn't in place when I started out. Being in the field and confronting questions and problems and trying to solve them, that’s what really taught me the most.

What was the biggest career risk you took? Obviously there are different kinds of risks, there’s the physical and also the psychological. When I began working with the media it was a different culture to the documentary process I’d come from. The risk, specifically with Nicaragua, was that my judgement to stay for an extended period of time was not understood. As a career choice it might have been better to move around a lot to different kinds of conflicts in that classic photojournalistic way. But I didn't really define myself like that. I wanted to invest and to immerse myself.

Which of your personal projects taught you the most? That’s a difficult question because I learn such different things from each project. When I was doing the work with carnival strippers, taking the time to build relationships was probably the lesson. But I’ve learned the most I guess from the Nicaragua work because time has been such a factor in my perspective.

Do you consider you have a particular style? I have an approach, but I’m not interested in style per se. I’m not sure I want people to be thinking this is a Meiselas photograph versus being engaged with what’s in the frame. My intent is to be successful in creating a kind of narrative space.

How do you define approach? It begins with finding something I’m curious about, often for reasons I’m not even sure of. It could be a particular group of people such as a project I did very early on, that few people know about. It was on a group of Santa Claus’ from the Bowery in New York near where I live. Or it could be about a place like Nicaragua, a culture in transition, a social conflict evolving. I’m drawn often to history and the evolution of an historical process like in Kurdistan. So my approach is building off that curiosity a set of relationships and engaging over time.

Can you define what has been the most artistically or personally satisfying work that you’ve done? I can’t judge one project over another. I’m not invested in having the same style or representation of the work. In fact I am more committed to exploring different approaches to represent the ideas I’m trying to make more visible. The aesthetics may change, so for example the work I did on the border of the US and Mexico was done with a panoramic camera, which creates a different dynamic. I think the aesthetics are influenced by what I’m trying to achieve with the work.

When you started out did you have an idea of what you wanted to do, did you think you were having a career? No not at all. First of all I started doing photography in a teaching environment and I was very interested in what we called at the time visual literacy. At that time I was not so much focused on my own work, although I was doing that on the side; that’s when I began the carnival stripper work. I stayed with teaching for a number of years, but I didn't see myself as a teacher in the long term. I didn't have a road map to how to be a photographer for life. That’s what I’ve done but I didn't know how to get there.

What turned out to be the most helpful thing you did to advance your career? The invitation to join Magnum was a definite shift and created many different kinds of opportunities, but most importantly a community with which I’ve related for forty years. There’s something about Magnum’s integration of multiple generations, which is particularly special and watching those lives evolve, and looking at the sustaining choices they’ve made in their practices, that’s invaluable. It’s not always what you talk about, but what you see around you. There’s a lot of diversity in Magnum more than similar notions of photography.

What's the most important thing you could tell someone about creativity? That it comes from within, it’s the process of engagement with what you see, and it’s about interaction. Ultimately creativity is solving the problems you create for yourself.

What’s your next big challenge in the world of photography? Participatory media interests me a great deal. I’ve just reprinted the third edition of the Nicaragua book with Aperture, which will have a modest augmented reality element. The pages of the book have icons and you download a free app and from the image on the page you can link to a short film clip from the film I made ten years after the first Nicaragua book. So you’ll have this interaction of a still photograph and the moving image. I’m quite curious to see how that activates audience engagement with the material.

Susan at the Magnum book signing at the Aperture stand at Paris Photo 2015

(C) Alison Stieven-Taylor

No comments:

Post a Comment